Economic formulations of the population question can be illuminating — perhaps more for what they tell us about economic science than about population dynamics. One specimen of this point is found in that the rise of late European civilization might be reasonably attributed to a massive population die-off. The development of significant trade between Europe and Asia during the Fourteenth Century brought with it waves of bubonic plague resulting in what might well have been history’s greatest sudden reduction of a large human population.

A lengthy period of exhausted feudalism preceded these events. It was characterized by endless and pointless wars that we may take as indicia of almost all Europeans living in economic niches so limited as to approach the brute survival of a Malthusian stasis. When mercantilism surpassed feudalism as the basis of economic organization, expanded socio-economic niches opened-up in Mediterranean port cities for the population to fill.

Trade supported the new urban concentrations economically, but these more commodious economic niches were to prove technically unsustainable in one unforeseen particular: unimproved rural sanitary practices became deadly when transported an urban setting. When the plague bacillus arrived with cargoes from Asia it found plentiful hosts among the vermin whose ecological niches had multiplied next to those of their human neighbors.

The countryside’s more primitive feudal technique could not support a retreat of these recently-multiplied urban masses. Decade after decade they died in place, while the plague that killed them also depopulated the countryside. A large population had been trapped outside the possibility of material survival.

This contraction toward an earlier medieval technology was arrested by a new science of urban sanitation. When concentrated urban living became safe, the socio-economic niches provided by mercantilism re-opened to a population that plague had reduced by a third or more. Labor, in desperately short supply relative to the opportunities for profit, bargained itself into spacious economic niches that hoi polloi had not known previously. The Renaissance was launched by talent discovered among newly mobile common people; a general principle of material progress was established; and Northern Europe was on its way to becoming another of history's great world empires.

Having overcome a major technical barrier to urbanization, economic mercantilism found greater opportunities across the Atlantic than in Mediterranean. Its expanded logistical needs could only be met by vastly larger urban populations concentrated in Atlantic port cities. Had urban sanitation not been developed in response to the plague, then Amsterdam, Cadiz, and London could not have grown larger than Genoa or Venice. The ensuing period (down to, say 1960) has seen human wealth per capita increase exponentially even while the human population was also increasing exponentially. During this time, mankind was not only clever enough to multiply the number of his socio-economic niches, he has done so while vastly expanding the comfort of each niche.

Is there, then, such a thing as overpopulation? The notation for economics’ contribution to this question is set forth in the elementary production function below.

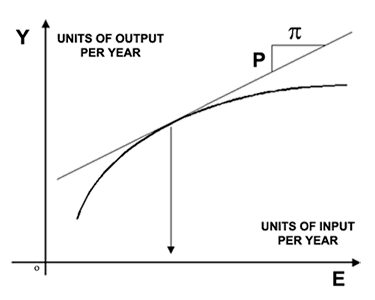

Here we see that an input E is related to an output Y such that its utility diminishes at the margin of its application. Economic reasoning proceeds to estimate the relative value of Y with respect to E by the slope ¶Y/¶E of this downwardly concave curve:

where P is the value of E and p is the value of Y. As Y and E increase together, E’s value P must decrease in relation to Y’s value p.

The population question admits to economic analysis when Y comprehends all products, E stands for the input of labor, and everything else is expressed in the functional relationship between Y and E. When viewed in this way, the economic causality referenced in the above plot depicts a relationship between population and wealth. If population increases are modeled by increasing E, then they entail a decrease in labor's value P relative to the value of all things p. Imaging this tradeoff to be fixed by a constant technology creates a representation for the late medieval period in which E had advanced to a Malthusian limit wherein labor’s marginal product P/p approached subsistence.

Rejection of strict economic analyses for the population question must somehow deny the economic frame of reference sketched above, e.g.: either the functional relationship posited for Y and E cannot be drawn; or, if it could be drawn, we would see that the curve in our diagram has been moving upward more rapidly than the value of E has been moving outward.

Any lengthy historical record is thick with a great many particular instances in which the outward impulse of E affirmatively causes the upward translation of our putative relationship between Y and E. This general tendency was winnowed out of the record by economist Julian Simon; and he popularized it quite ably in his later work.1 The possibility of keeping technological progress ahead of population apparently extends for a period that we cannot yet define; and there are persistent, systematic reasons for expecting more of the same.

Generally expansionist Europeans are nonetheless periodically tempted by technical advances that prove unsustainable. When this happens, mere biology requires that large numbers of people die before their time — a requisite accomplished by war whenever a threatened population has time to organize for it. The Irish potato famine of 1845-47 exemplifies a localized reprise of Europe's great plague. Any number of contemporary instances of technical overreach are seen wherever Europe, with its cultural experience, has withdrawn from its former colonies.

Where economics sees humanity as nothing more than an input to the economic system, it does not cognize that labor’s price cannot go below biological subsistence without plunging the entire social system into chaos. We may also note that the strictly materialist case for population control collapses to a conclusion that humanity is better off insofar as its population is small, and therefore presumably most happy when entirely absent. American Shakers are but one of the many evangelical sects who have followed their idolatry of reason into this oblivion.

In sum, we find elementary economic principles sufficient to establish that populations can exceed the carrying capacity of a certain locale under certain circumstances. But economics cannot be certain that such circumstances will inevitably check population growth because economic theory does not reckon changes in its technological boundary conditions. As a corollary, we can be certain that economic growth is accomplished by a diminution of population; but economics hardly suffices to evaluate the often terrible means by which diminution is accomplished.

To this uncertain knowledge, we append an observation that capitalism is not just another principle of economic organization. It is itself a technology; and, moreover, it is the meta-technology by which the industrial arts are optimized for a population that is now hugely reliant on capitalist efficiency per se. Thus the periodic failures of capitalism in modern times, when associated with the wars they precede, are properly analogized to the murderous technological failures of more remote historical periods.

_____________________

1 Julian Simon and Herman Kaufman, 1984.